While Numata managed to mark his time at Heart Mountain photographically, albeit sparsely, many Japanese Americans have empty pages in their family photo albums because they did not have access to cameras while they were incarcerated. Representations of rites of passage are missing. Casual snapshots were not taken. Numata’s photographs made during the decades he spent in Chicago repopulate those pages and serve multiple functions. At the time they were made, they recorded the growth of the Japanese American community and could be used instrumentally to illustrate the Chicago Japanese American Year Book, for example. But they could also be understood to serve a more symbolic function. Numata’s case file reveals how he struggled with the imposed categories of loyal and disloyal. Numata’s initial refusal to answer the Leave Clearance Application affirmatively and his request for expatriation could be read as a form of protest through negation. His photographs of Chicago, however, participate in protest via affirmation. As Lane Hirabayashi writes, “WRA resettlement policy can be seen as a pernicious form of forced Americanization that was inherently inimical to any positive dimensions of Japanese American identity, culture, and community.” Despite the government’s desire to use relocation as a method of ethnic dispersal, Numata’s photographs depict the makings of a nascent Chicago Nihonmachi (Japantown). They are rife with the expression of Japanese American identity, culture, and community.

With increased scrutiny to the Numata collection, perhaps the photographs of a fairly unknown photographer can also play a role in “reclaiming,” in Hirabayshi’s terms, as part of a “post-Redress politics of interpretation.” Hirabayashi concludes his study of WRA resettlement photographs, titled Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens, with a desire to read his own family’s story into a photograph of Issei men at a home for seniors in San Francisco. He is not directly related to those pictured but he can project his own family history into the frame. Perhaps Numata’s photographs too can give a fuller picture of post-war Japanese American life, depicted by someone who worked to build that life from within as both a participant and an observer.

Despite the tense encounters Numata had with camp officials and the barriers he faced in leaving Heart Mountain, at the age of 71, he decided to attend a camp reunion. In 1989, Jim Numata booked a trip to Reno, Nevada. He ordered ahead for prime rib at dinner and had a ticket for the Sunday farewell brunch. (LINK TO: Images 4.1, and 4.2) The pleas from the Heart Mountain reunion committee had worked. In all caps the invitation warned, “DON’T MISS YOUR OPPORTUNITY TO ATTEND WHAT MAY BE THE LAST REUNION.” (LINK TO: Image 4.3) To lighten that morbid message, attendees were encouraged to arrive on Friday for jitterbugging at the “Rec Hall Block Dance.” At Saturday’s banquet, Bill Hosokawa gave the keynote address titled “Forgiven, but not Forgotten.” (LINK TO: Image 4.4) Numata made the trip alone and held onto his Bally’s guest card, the program, and other documentation of his trip.

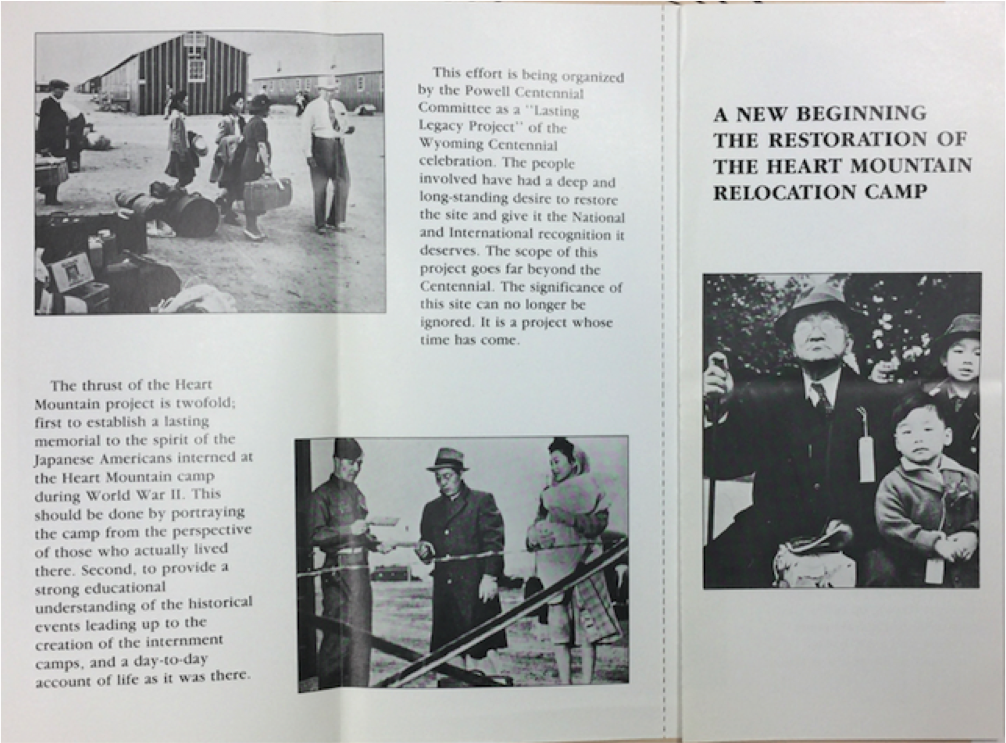

Judging from the list of attendees, which numbered approximately 1000, the aging Nisei likely felt a sense of nostalgia. Numata also retained documents from his trip that include a survey asking how a proposed Heart Mountain Memorial Park should be constructed, and a brochure for selling photo books of different camps called “Official Historical War Relocation Authority Photographs and Documents” by TeeCom productions. (LINK TO: Images 4.5, and 4.6) The brochure for the photo books warned of that the original photographs were deteriorating and that “In another decade all photographic records of the evacuation and internment will be but a memory.” It would not have been possible to know that twenty-five years later, the extensive collection of WRA photography would be preserved and digitized, accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. But what James Numata would most certainly have known at the time was that the photographic archive that he had created over his lifetime needed a home. Ten years after his trip, and two years after Numata’s death, the Japanese American Service Committee became that home.